If you work in fashion, September and February are significant, the two months of the year when the parameters of a working day disintegrate and phones ceaselessly ding. For these two occasions, fashion professionals are alive and enigmatic, sustained by the anticipation, the buzz, the blue backlight of a laptop, and an unhealthy amount of caffeine. These months are steeped, until sodden, in a tart concoction of overworked excitement. But, of course, everybody knows this. These are the sourer details of the industry, as dramatized by Hollywood in the likes of The Devil Wears Prada, Sex in The City or The House of Gucci. What goes more unnoticed, and is impressively glossed over by consumers, is the constant inundation of branding and calls to purchase that make their way onto the screens of the general public during these earmarked months. Consumer interaction with fashion, even amongst those who for the rest of the year have no interest in the industry, is high and thriving in September and February, due to the multi-level strategies brands adapt to make the most out of this window of opportunity. With the SS24 fashion month elapsed, and the FW24 edition around the corner, it seemed a fitting moment for GLITCH to reflect on the concept of the biannual, multi-continental fashion stream. GLITCH wants to dissect its purpose, its success, and if perhaps it is time for change against the traditional two part calendar.

The Digital Value of Fashion Week

It is increasingly obvious that fashion week has become a multidimensional period of activation; fashion week is no longer for those on the ground, but also for those in the cloud. The original purpose of fashion week was to be a unified showcase of fashion houses’ creations for the impending season, the grandest of trunk shows, attended by the crème de la crème. But, as the budgets and staging have got bigger and better, the in-person fashion week effect has conversely been dampened. With the growth of the interconnected world, there is limited reason for fashion shows to be acutely attendee-oriented; nowadays, the footage is streamed, and the photography diffused in the space of a breath. A teenager in Shanghai can see the Dior collection live-streamed from Boulevard de Courcelles almost instantaneously on YouTube.

The pace of the media typed, or the coverage snapped, and the general dissemination of information has hastened to a barely manageable pace. Media outlets tweet throughout the shows and journalists turn over copy within 20 minutes of taking their departure cabs. So, within this frenzy of insight, content, and insta-worthy spectacles, how do brands stand out on the explore page, in the headlines, and the words on the public’s lips? How do they secure that “watchable” and “viral” status? And most importantly of all, how do they create imagery that is markedly different to what has come before? Nobody is interested in another slim model, in another slim dress.

Why Fashion Is Performing For Online Audiences

The answer lies in the art of performance, which has somewhat controversially become enmeshed with the art of shocking, wave-making and stir-causing. Fashion houses are turning to big flashy displays, toying with expectation, and off-beat showman tactics, to make their name pop against the overcrowded sea. Aptly summarised by Charlotte Gillet, a Marketing Analyst at Launchmetrics, “Fashion shows are now just as much about a brand’s cultural capital as they are about the collections they introduce”. In our current environment, this cultural capital lies in the digital image and footprint generated by a brand, in other words, the key is how successfully the experience can be translated into hooking digital coverage.

Launchmetrics use a trademarked algorithm that measures MIV, Media Impact Value, of certain staged events. The data they collated from SS24 showed Paris Fashion Week to be the top performer warranting a $499M in MIV. Their data also showed Instagram to be the most powerful channel for generating these ROI and Media Voices were the most powerful profiles, with Influencers and Celebrities being a close second. The digital value of Fashion Week seems in many ways to be uprooting the physical production value of Fashion Week, and this transition is being marched forward by an army of online personalities. Ralph Lauren, Burberry, Gucci, and Dior generated the largest metrics for MIV at the corresponding Big Four fashion week, with Dior settling into 1st position with a staggering $58.7M MIV generated from this year’s fashion week activation. Rachel Arthur, a journalist for the Business of Fashion, calls this generates value the “brainprint” of fashion shows are being organized and created with this knock-on effect for consumption at the centre.

Who Is Fashion Week Actually For?

This digital potential of fashion week events leads us to ask the question: Who is fashion week actually for? Is it for the front-row attendee or the Instagram scroller? And if the latter is the case, then are we nearing an era where fashion weeks may take place completely in the digital world, free from the costs of event space, models, and tangible production, and effortlessly broader in the scope of imagination? To create a wide rippled impact, brands are beginning to curate their presentations with the Instagram onlookers in mind. But whilst Instagram is a broad and diverse community, it is also an oversaturated one, where content and coverage can become lost and hidden amongst the consistent influx of new and buzz worthy media.

The Power of The Influencer

Fashion week orchestrators are certainly beginning to rethink the most budget-friendly ways to cause a ruckus on the global stage. After all, in 2023, shock seems to be trendy. Influencers, for all the stick they receive, have in many ways facilitated this globalisation of fashion, democratising a once highly walled industry. The influencer cohort can disseminate a muti-lens view of different events across the world, accessible to anyone and everyone. But influencers act as more than just portals into a ticketed or guest-listed space, they also can reinvigorate brand energy, redefine a brand image, or change the strain of conversation. Influencers, like it or not, breathe life into brand personality, and this is the reason for their ceaseless growth, with the influencer market value now standing at an impactful 21.2 billion dollars. Yet, at the same time, despite the wealth they can generate, they remain but an army of vital pawns in this inauthentic chess game of fashion stunting.

In 2020, we were assessing the power of digital amidst a COVID-ridden world. This was when Aniye By’s one guest show at MFW, attended solely by Chiara Ferragni, was a big step in the digitization movement, and Burberry’s infiltration into Twitch, as one of the first luxury brands to adopt livestreaming, seemed pioneering. But now, in reality, the majority of major fashion houses have absorbed the need to bend the fashion walls and lean their shows into a publicly available digital space. In 2020, journalist Maddy Raedts penned that influencers are “primed to lead brands towards a better future for fashion” “helping them further evolve to new consumer needs” in an article for Forbes that applauded the new lease of life influencers were giving fashion week. And, whilst their contributions can be applauded, and charted financially, at GLITCH we always like to starkly evaluate the contrary, and debate against the norm.

The Muddled Position Of Fashion Weeks: to digitise or not?

For GLITCH, it seems obvious that at present, the fashion industry is straddling a muddled position, and one that seems for us, as a forward-thinking magazine, painfully unsustainable. As it stands, brands are leveraging the power of digital dissemination and global audiences without fully converting to wholly digital forms of exposition. They are still burgeoning the costs and consumptions of live fashion show activity, but their aims and projection are intended more so for the public behind the screens, than the FROW invitees who have already been gifted and endorsed with the product.

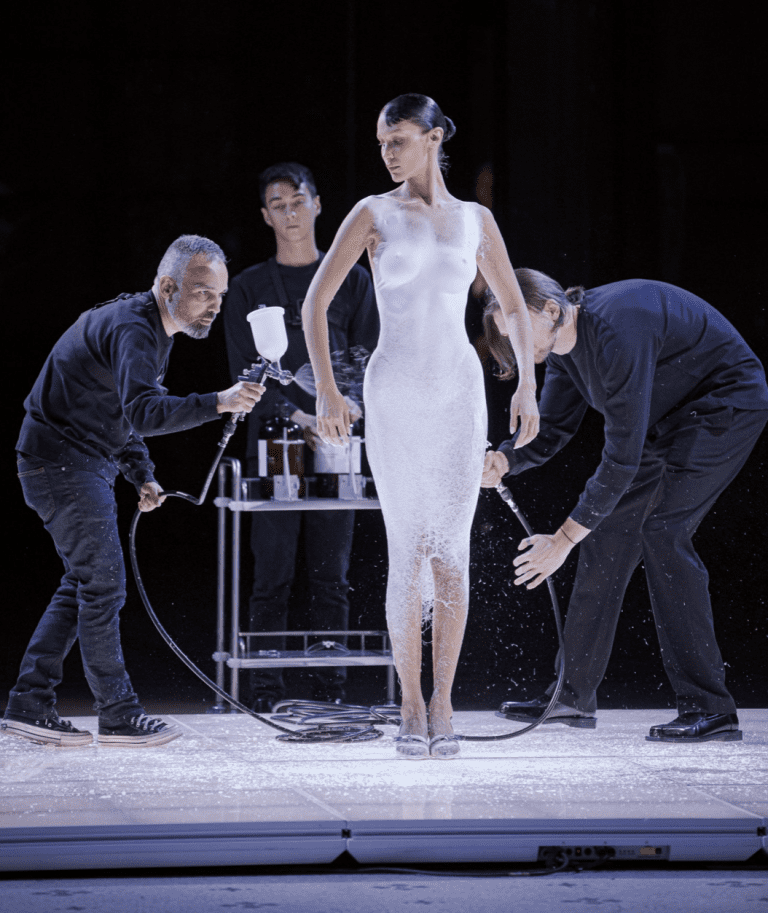

The aim, ultimately, is to reach the bang average woman, who, supposedly, after seeing Bella Hadid spray painted in a dress, will be imprinted with the unshakeable memory of the Coperni name and purchase one of their handbags on her next payday. As farfetched as that cycle may seem, it is accurately, and profoundly backed by data. In psychology, academics refer to the mere exposure effect, a finding by Robert Zajonc in 1968, that concluded that people can reap enjoyment from something purely as a result of continuous exposure. That is to say, advertising of a viral nature can reap a more positive response, the same consumers see the content over and over again and grow to have a stronger relationship with it – it is a similar phenomenon to how hit songs are made. This impression timeline is real, and something to capitalize on.

But what on earth does Bella and spray paint have to do with Coperni’s shoppable collection – absolutely nothing. But it is memorable, impressionistic and click-worthy. Culted writer Robyn Pullen defines this performance trend as “employing a “viral moment” in your show, a stunt that is so certain to gain the internet’s attention that it’ll be posted and reposted into oblivion.” And this is the tactic that has been adopted as the current high road to successful fashion marketing.

The Fashion Week Phenomenon: Physical Stunts For Digital Effects

Unfortunately, fashion weeks now seem to be riddled with this tactic, and as such it is becoming “over-egged”. Stunting has become competitive, overdramatic, and quite frankly, deeply unrelated to clothing and brand personality, in an attempt to just grasp an extra second of attention from boggle-eyed social media onlookers. SS24 in particular capitalized on the wow factor of the stunt. It began in New York, where Elena Velez’s models wrestled in mud. Next, in London, Burberry took over the city with a themed café and tube station that faced criticism for appropriating working man’s culture. In Milan, Diesel hosted an unconventional 7,000-guest party, and Prada got experimental with slime. And Paris offered a finale to the month of theatrical performance, as Christian Cowan sent disoriented fur-ball models tumbling into the Front Row, and Courreges had models stamping through a thin plaster floor.

High Snobiety quite aptly summated the whole 4 week period with their damning headline that read “Clothes Came Last At Fashion Week SS24”. That being said, there is a strong data-driven correlation suggesting that brands that did invest in the stunt, often performed very successfully in the league tables of Media Impact Value and Return Of Investment. It seems natural that the more oriented and tailored to photography and recording your event is, the more successfully it is going to be covered and tracked, and the more successfully it is going to perform and resonate with the audience behind the screen.

The disjuncture seems to be that there is a clear target for a digital audience, but brands persist in curating the expensive, and resource-heavy, tangible experience. Arguably, the pandemic spurred and motivated a conversion to digital presentation, but according to many the post-pandemic environment isn’t quite the same, and has seen the emergence of two polarised camps. Some are pioneering tech-led eventing, and those who are adamant that the tangible can’t be eradicated. In the current environment, there seems to be a disconnect between the two, that almost numbs the legitimacy of fashion week, when it is so obvious brands are simply vying for online virality.

The Future of Fashion Week

In this way, could it be said that Instagram is taking over fashion week, and will there come a point where the two can’t be separated? What’s more, will the authenticity of good clothing become redundant amidst the spectacle of the fashion circus? On a further point, is there even any point in worrying about the unsustainable practice of in-person eventing, when the overconsumption encouraged by the digital effect of fashion week is generating just as scary a climate cost?

Fashion and Fashion Week seem to now be about aggravating popular culture and playing on human tendency. It is not clear what exactly the future of fashion week is, and how long the biannual calendar will remain in roll. What can be said for certain is that as the digital leaks into our physical, the advertising nudge to shop and overspend is no longer being constrained to two months of the year, nor key fashion week epicentres, but is rather gnawing at everyone, always. In this entangled world of advertising, how are shoppers supposed to make informed and authentic decisions, and could we enter an era of the lost consumer?

Written by Hebe Street from GLITCH Magazine